Rateliska Sesquicentennial Park was created to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the transfer of the imperial capital to Sensuka. These magnificent pleasure gardens are located on the island of Rateliska, which lies directly across Rejoma Bay from the Korkidéh district, at the southwestern end of the city. One may reach the island via the ferry boat that leaves from Karipaza Square (See n. 23) and which disembarks directly at the entrance of Rateliska Park.

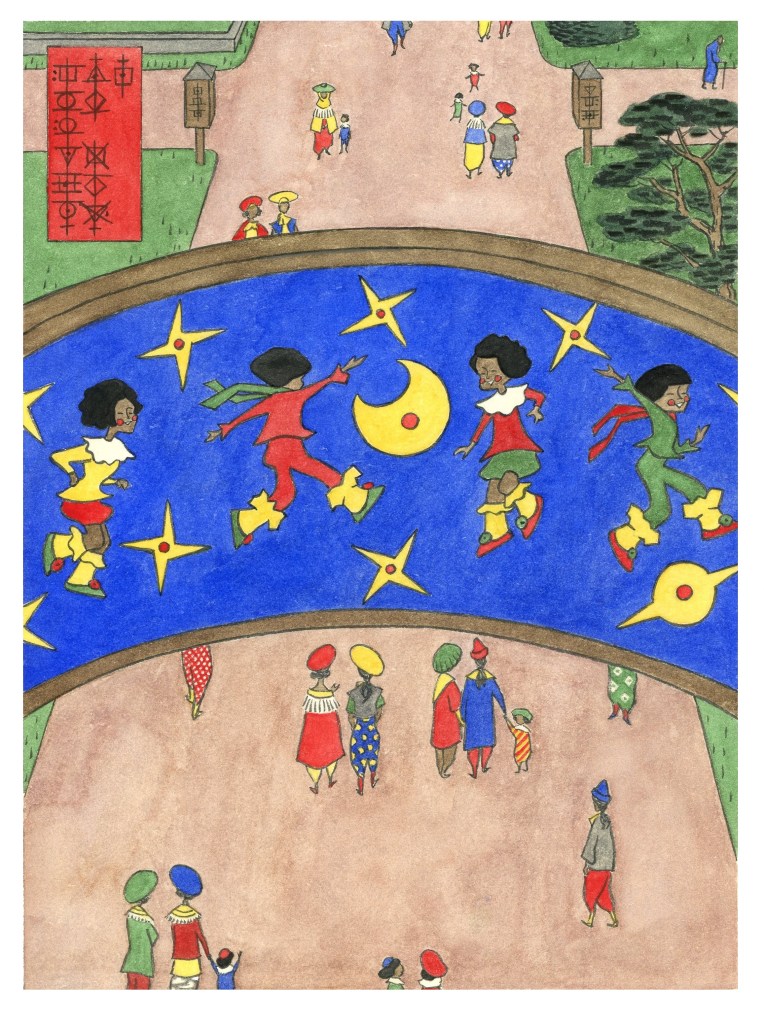

Marking this entrance is a wooden arch supported by two stone pillars. Running along the arch is a painted frieze depicting little girls and boys at play against a star-studded blue background. In this print, the artist has placed the frieze at the very centre of the composition, as though to call special attention to it. This may seem surprising, given that the painting would appear to be of little intrinsic aesthetic interest—an assemblage of generically ebullient child figures in conventionalized poses, executed in a popular commercial style from fifty years ago. The bright, primary colours are typical of that era as well, although the pure ultramarine background is perhaps somewhat unusual (It should be noted, however, that the painting is in reality far more faded and weatherworn than as depicted here). The way in which the children seem to be running and jumping amid a wholly immaterial landscape composed only of sky, stars, and planets, can also perhaps be momentarily arresting. Such cosmic playgrounds were also very much an aesthetic trope of the period, however, almost to the point of cliché.

Why, then, would of the author of the Famous Views choose to highlight such a banal and even insipid image? One possibility is that the frieze holds a powerful nostalgic appeal. A visit to Rateliska Park has been a popular destination for family outings since the time of its opening. In the minds of many Sensukans, the painted frieze over the archway may be associated with pleasant childhood memories. One of art’s greatest powers is undoubtedly its capacity to evoke nostalgia, whether for a time in our own lives or for the historical period in which the work of art was created. (It matters little, in the latter case, whether we lived through that period or not. We can be nostalgic for an era we have never experienced, if only owing to our memories of our first discovery and awareness of it.)

But is it not an extraordinary thing, when one comes to think of it, how our deepest feelings relating to another time—all that strange mix of comfort and sadness, and the mysterious yearning for something else that seems to lie behind it all—could come to find their perfect visual embodiment in the stylized rendering of a moon or the blankness of a geometricized grin? What is one to do, as an artist, when one realizes that that which one would most like to express, that which all one’s art, perhaps, has ultimately been striving for, could never be captured one iota as well as in such pedestrian and indeed almost embarrassingly kitschy images? This print may be intended as an acknowledgement of such a defeat.